Roshi: a CRDT system for timestamped events

Let’s talk about the stream.

The SoundCloud stream represents stuff that’s relevant to you primarily via your social graph, arranged in time order, newest-first. The atom of that data model, an event, is a simple enough thing.

- Timestamp

- User who did the thing

- Identifier of the thing that was done

For example,

- At 2014-04-01T13:14:15.034Z,

- a-trak

- Reposted track skrillex/duck-sauce-nrg-skrillex-kill

If you followed A-Trak, you’d want to see that repost event in your stream. Easy. The difficult thing about time-ordered events is scale, and there are basically two strategies for building a large-scale time-ordered event system.

Data models

Fan out on write means everybody gets an inbox.

That’s how it works today: we use Cassandra, and give each user a row in a column family. When A-Trak reposts Skrillex, we fan-out that event to all of A-Trak’s followers, and make a bunch of inserts. Reads are fast, which is great. But writes carry perverse incentives: the more followers you have, the longer it takes to persist all of your updates. Storage requirements are also quadratic against user growth and follower count (i.e. affiliation density). And mutations, e.g. changes in the social graph, become costly or unfeasible to implement at the data layer. It works, but it’s unwieldy in a lot of dimensions.

At some point, those caveats and restrictions started affecting our ability to iterate on the stream. To keep up with product ideas, we needed to address the infrastructure. And rather than tackling each problem in isolation, we thought about changing the model.

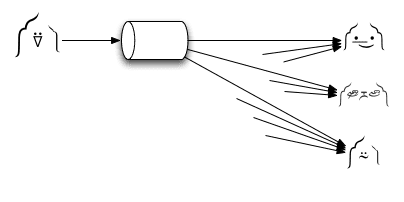

The alternative is fan in on read.

When A-Trak reposts Skrillex, it’s a single append to A-Trak’s outbox. When users view their streams, the system will read the most recent events from the outboxes of everyone they follow, and perform a merge. Writes are fast, storage is minimal, and since streams are generated at read time, they naturally represent the present reality. (It also opens up a lot of possibilities for elegant implementations of product features and experiments.)

Of course, reads are difficult. If you follow thousands of users, making thousands of simultaneous reads, time-sorting, merging, and cutting within a typical request-response deadline isn’t trivial. As far as we know, nobody operating at our scale builds timelines via fan-in-on-read. And we presume that’s due at least in part to the challenges of reads.

Yet we saw potential here. Storage reduction was actually huge: we projected a complete fan-in-on-read data size for all users on the order of a hundred gigabytes. At that size, it’s feasible to keep the data set in memory, distributed among commodity servers. The problem then becomes coördination: how do you reliably and correctly populate that data system (writes), and materialize views from up to thousands of sources by hard deadlines (reads)?

Enter the CRDT

If you’re into so-called AP data systems, you’ve probably run into the term CRDT recently. CRDTs are conflict-free replicated data types: data structures for distributed systems. The tl;dr on CRDTs is that by constraining your operations to only those which are associative, commutative, and idempotent, you sidestep a lot of the complexity in distributed programming. (See: ACID 2.0 and/or CALM theorem.) That, in turn, makes it straightforward to guarantee eventual consistency in the face of failure.

With a bit of thinking, we were able to map a fan-in-on-read stream product to a data model that could be implemented with a specific type of CRDT. We were then able to focus on performance, optimizing our reads without becoming overwhelmed by incidental complexity imposed by the consistency model.

Roshi

The result of our work is Roshi, a distributed storage system for time-series events. It implements what we believe is a novel CRDT set type, closely resembling a LWW-element-set with inline garbage collection. At its core, it uses the Redis ZSET sorted set to store state, and orchestrates self-repairing reads and writes on top, in a stateless operational layer. We spent a long while optimizing the read path to support our latency and QPS requirements, and we’re confident that Roshi will accommodate our exponential growth for years. It took about six developer months to build, and we’re in the process of rolling it out now.

Roshi is fully open-source, and all the gory technical details are in the repository, so please do check it out. I hope it’s easy to grok: at the time of writing, it’s 5000 lines of Go, of which 2300 are tests. And we intend to keep the codebase lean, explicitly not adding features that are outside of the tightly defined problem domain.

Open-sourcing our work naturally serves the immediate goal of providing usable software to the community. We hope that Roshi may be a good fit for problems in your organizations, and we look forward to collaborating with anyone who’s interested in contributing. Open-sourcing also serves another, perhaps more interesting goal, which is advancing a broader discussion about software development. The obvious reaction to Roshi is to ask why we didn’t implement it with an existing, proven data system like Cassandra. But we too often underestimate the costs of doing that: costs like mapping your domain to the generic language of the system, learning the subtleties of the implementation, operating it at scale, and dealing with bugs that your likely novel use cases may reveal. There are even second-degree costs: when software engineering is reduced to plumbing together generic systems, software engineers lose their sense of ownership, which is the foundation of craftsmanship and software quality.

Given a well-defined problem, a specific solution may be far less costly than a generic version: there’s a smaller domain translation, a much smaller surface area, and less operational friction. We hope that Roshi stands in evidence for the case that the practice of software engineering can be a more thoughtful and crafted process. Software that is “invented here” can, in the right circumstances, deliver outstanding business value.

Roshi was a team effort. I’m deeply indebted to the amazing work of Tomás Senart, Björn Rabenstein, and Johan Uhle, without whom Roshi would have never been possible.